There was more bad news for the FOMC over the past few days beside the once again near-zero GDP estimate. If the labor market were truly growing as is claimed, we should be finding “inflation” in a broad set of different economic views. From the standard inflation calculations to various estimates for wages or income, by now it should be unquestionable. The major employment series have been in overdrive for more than two years now, plenty of time to digest any lagged effects of massive labor gains.

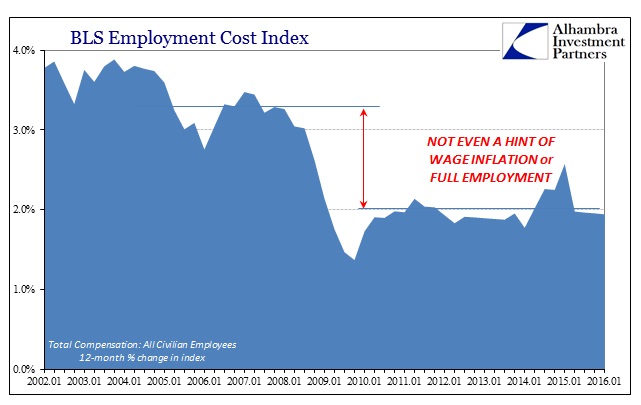

The Establishment Survey picked up at the start of 2014, with March and April that year figured at +272k and +310k, respectively. Those numbers suggested that the economy had shaken off the prior year’s (2013) uncertainty posed by the taper drama and the related financial disruptions. Since that time, at best we have found only uneven and temporary suggestions that anything might be different with regard to inflation and economic “slack.” Early last year, for example, the BLS’s Employment Cost Index (ECI) picked up sharply in the first quarter, rising to 2.6% year-over-year and seemingly providing the needed evidence for the prevalent optimism about “overheating” at that time. That was how it was spun, as economist after economist claimed that the rise was the definitive arrival of ultimate monetary success.

That “bump”, however, disappeared as quickly as it showed up, as the rest of the year dropped back again to 2%, which seems to be the attractor level for this index. The latest update in the ECI for Q1 2016 is slightly less still, at just 1.9% Y/Y.

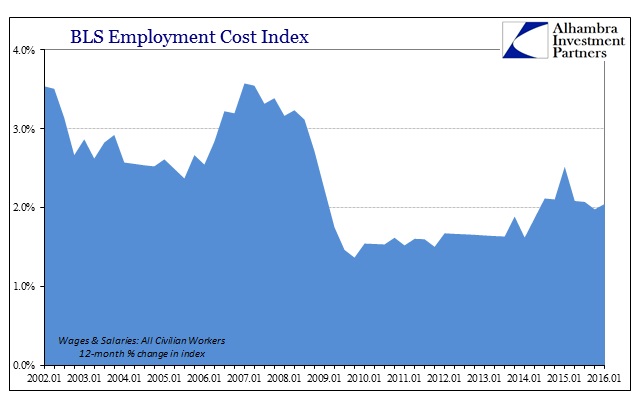

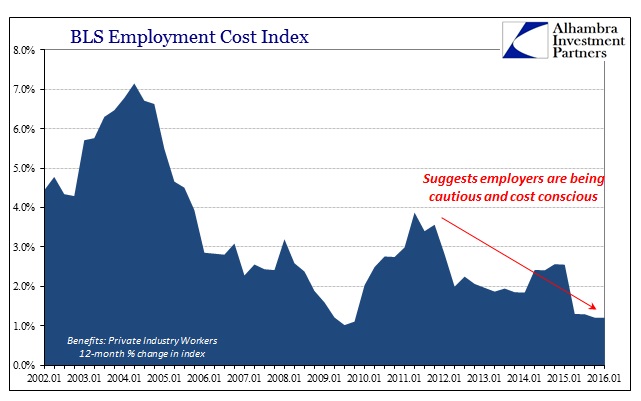

At less than 2%, the increase remains 1.5% below the average of the pre-crisis period when the economy last appeared to be matching expectations provided by the unemployment rate. There has been a small increase in the subcomponent for wages and salaries, but it isn’t clear if that is significant especially since it is more than fully offset by a decline in measured gains in employee benefit costs. At best, it suggests that employers are still as cost attentive as ever and if they are deploying even modest wage increases they are immediately and completely compensating wherever else possible. That does not suggest the end of “slack” or a highly competitive labor environment.

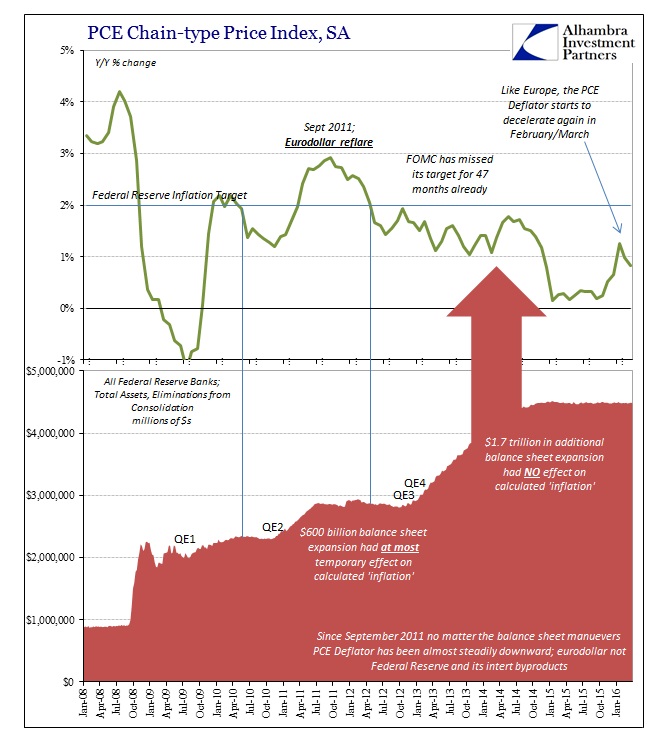

In the broader economy, calculated inflation through the Fed’s preferred metric, the PCE Deflator, continues its astounding underperformance. To my knowledge, the Federal Reserve has yet to disallow its own ability or remove its inflation target, and yet the PCE Deflator fell below 1% year-over-year once again in March. That represents the 47th consecutive month below the set 2% inflation target, meaning that as powerful as the Fed supposedly is in mainstream lore it has a very peculiar way of showing it. That is even more curious given that there were two additional QE’s offered (amounting to $1.7 trillion in balance sheet expansion) in tandem with continued interest rate “accommodation” the entire 47 months.

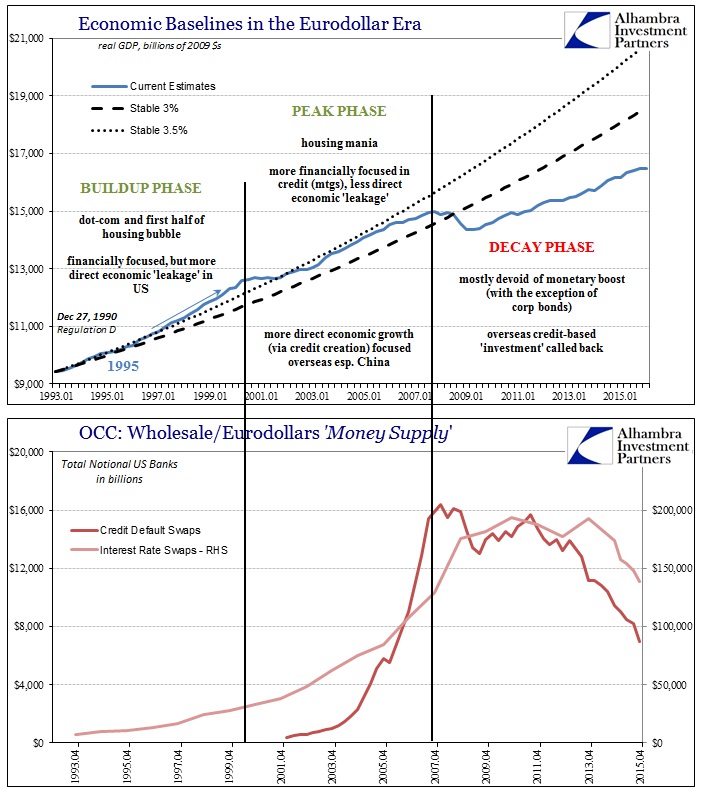

It all adds up to a dispositive lack of evidence for either the recovery or monetary competence. The 2% target, whether or not you agree with the intention (and I really, really don’t), is the primary task given to the agency. A four year deviation is not some temporary problem to be waited out, it is indicative of serious disruption in the expected monetary flow (and once again points to the fact that they really don’t know what they are doing). That there would be only worsening economic circumstances alongside that structural deformation is unsurprising.

Going four years without hitting your inflation target, and actually having your preferred inflation measure only get further away, despite $1.7 trillion in additional “money printing” can only mean that central banks aren’t what they are made out to be. That possibility does seem to be creeping into the mainstream conversation, as broken expectations can only foster blind faith for so long.

And while wages, salaries and benefits were stuck in neutral, the index showed that employer costs for health care were on the rise, gaining 3.3 percent in the period compared to a 2.5 percent increase for the previous 12-month cycle…

Along with the ECI data, personal consumption expenditure growth, another favored Fed metric, remained weak. Core PCE, which excludes food and energy costs, rose just 1.6 percent annualized, while the headline number was up 0.8 percent year over year. Consumer spending was little changed for the month, while savings hit their highest level since December 2012.

Taken together, the numbers don’t provide a lot of impetus for the Fed to move anytime soon. Traders in the fed funds futures market are reacting in kind.

Despite a plethora of Wall Street economists insisting that a June hike is on the table, traders estimated the probability at just 15 percent, a decline of 4 percentage points on Friday morning alone. No month until December has a better-than-even chance for a rise, with November falling to 47 percent Friday.

“Wall Street economists” can continue to insist that all is well and orthodox economics not at all disproved, but all the evidence points to something else entirely.